I want to clarify a few important terms that get used to describe different types of training sessions.

A “tempo” session refers to a training effort that is focused on holding a consistent stroke rate and/or pace throughout. This could take the form of intervals or a single distance/time. Heart rate is not a focus on these types of sessions; however, in general, the heart rate will rise gradually throughout the session, and likely cross several “zones”.

Some examples of “tempo” sessions from our program include:

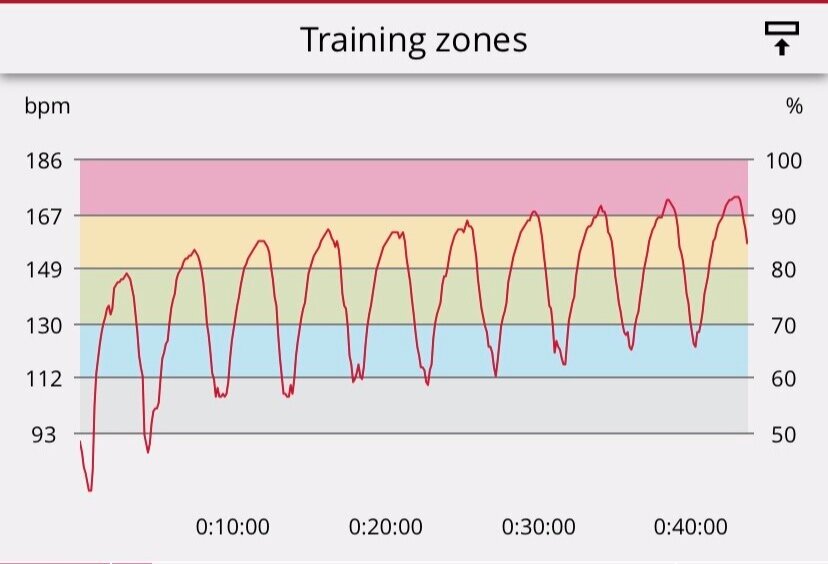

An example heart rate graph of a “tempo” session consisting of 10x 750m/rest 2min at 28 s/m. Notice the gradual and consistent rise in HR throughout the session.

10x 750m/rest 2min at 28 s/m

Target 2k PB pace + 7-8 seconds

or…

10k at 20 s/m

Target 2k PB pace + 17-18 seconds

A “steady state” session refers to a training effort that is focused on holding a consistent heart rate in a low or sustainable intensity zone. This is typically completed as a single distance/time, but intervals (usually longer) could be utilized as well. Pace and rate are not necessarily a major focus on these types of sessions; however, in general, your pace will likely slow down to maintain the desired heart rate zone (a positive split). In some cases, the lower the target zone, the more consistent the pace is likely to be.

Some examples of “steady state” sessions from our program include:

An example heart rate graph of a “steady state” session consisting of 2x 6000m at a target heart rate of 70% MHR.

8k to 15k (low, or open stroke rate)

Target 70-75% of max heart rate

or…

30min to 60min (low, or open stroke rate)

Target 75-80% of max heart rate

Both session types have tremendous value within our training program, and we utilize them weekly. What session to do (and when) is often the most challenging part of workout selection for our athletes. Every training cycle is different, and managing intensity is critical to finding success in this program.

The more often an athlete trains during the week, the more “steady state” sessions they should probably include. Let’s look at someone who trains on multiple machines, and completes 10 sessions per week. At least 5 or 6 of the sessions should be done at a lower intensity (SS). The other sessions can be comprised of tempo sessions, or threshold/speed/power development sessions.

Now, for comparison, let’s look at someone who only completes 3 sessions per week on one machine. This is probably the “minimum” dose to maintain general capacity on one of the ergs. Depending on the training cycle, as many as all three or as few as zero of the sessions could be steady state. In a purely “base building” cycle, all three could be long, steady efforts. If we are in a 1000m prep cycle, then all three will be comprised of either tempo sessions or threshold/speed/power development sessions.

In the end, the choice is on the athlete. By design, our program provides significant structure while allowing for the greatest amount of choice possible without diminishing the intent of the specific cycle. That’s the biggest feature of our yearly plan that is truly unique, and something we are proud to be known for within the online erg world.

A sample of our weekly programming. The colours indicate a sessions relative intensity and/or majority heart rate zone, where GREEN is typically “steady state” and around 70-80% of max heart rate. YELLOW/ORANGE usually includes “tempo” sessions and stroke power development, and RED is set aside for the harder sessions of the training cycle (which focus on race pace, or faster). The HR stats don’t always line up perfectly for all people, but subjective intensity (for the most part) follows the same pattern.